Caring for country

For Daryn McKenny, saving indigenous languages is about so much more than building a dictionary. It’s about preserving a wealth of traditional knowledge that benefits us all.

Daryn is a busy man with a schedule that is bursting at the seams, and it took a few attempts to set up our meeting. He had been out all night, filming koalas and just needed a few hours of sleep. Another time, he had been pulled into a conference at short notice. When we finally do meet, he sighs, “I just need a bit of a breather. I was supposed to write a government report last night, but ended up helping with a project in Cape York.”

Despite his fatigue, he is deliberate and concise in his demeanour but there’s an urgency to everything he says. Having dedicated the last two decades of his life to documenting indigenous languages, he carefully chooses his words, especially as we delve into topics that he is deeply passionate about.

Born and raised on Awabakal country, Daryn’s traditional ties lie with the Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri people. 22 years ago, he left his job at Telstra and started working in an Aboriginal community for the first time.

“When you grow up, you play football, you are chasing the girls, but then you get to the point where you want a bit more. So, when the opportunity arises, you take it, you learn and you become part of something different.

“I realised that as kids growing up, what we never had was language, and so we couldn’t understand the power of language and what it actually means. “We started what was to be a two-year project, run by indigenous people, to document the Awabakal language.

We would be going back to find words which had been published in old books, going back to the 1800s. And we were going to print a dictionary. It was a project of limited scope, but we were told that we weren’t good enough at doing this. That we didn’t have the skills or the education.

“I certainly wasn’t going to go back to school. But I realised that all we were lacking were the tools. So I went about creating them.”

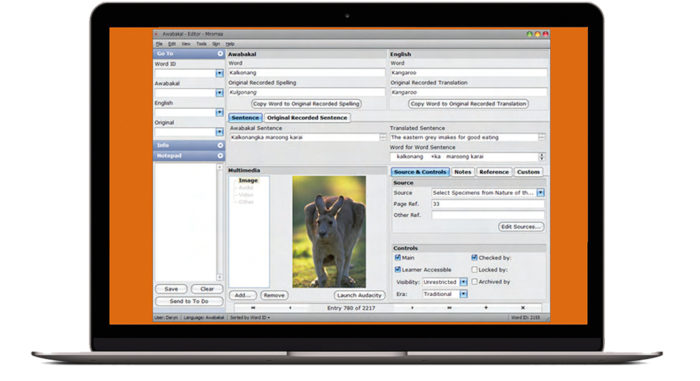

Daryn attended an indigenous language conference in Sydney in 2004 and shared what he had created. The software addressed a crucial void and triggered a wave of licensing requests from other indigenous language projects who were just as keen to use a system that would allow them to independently push forward with their work.

That was the start of the Miromaa software (Miromaa means “saved” in the Awabakal language) and the Miromaa Aboriginal Language & Technology Centre (MALTC), which, almost two decades later, is run by a team of four with the software used by 600 indigenous language projects around the globe.

Overlooked treasures

Miromaa has won many accolades over the years and even received recognition at the White House in 2016, during the National Youth Arts and Humanities Awards for Native Youth Ambassadors hosted by First Lady Michelle Obama.

“My definition of language today is different to what it was when I first started,” Daryn says as he hands me a small piece of stone, asking what it might be. I give him a puzzled look, and he explains, “it’s a cutting tool, a household item, created 15,000 years ago.

“Our country is littered with these kinds of artefacts, and they usually go unnoticed. But when they do get noticed, it triggers a tsunami. Archaeologists start digging, testing, carbon dating and cataloguing. Museums usually have way more artefacts than they can display, so chances are pieces will land in a box to be stored somewhere in their archives.

Read more in our Summer Edition of Hunter & Coastal Lifestyle Magazine or subscribe here.

Story by Cornelia Schulze, photography courtesy of Daryn McKenny and Miromaa Aboriginal Language & Technology Centre